VENDOR INCLUSIVE URBAN STREETS (VIUS)

THE PROBLEM

Street Vending has a historical significance in the Indian subcontinent. They are a memorable part of everyday culture to people form across generations. Yet as cities get built and develop, they seem to be consistently out of place, disorganised along roadsides and overflowing onto roads. News cycles of their evictions and people blaming traffic congestion on them are common hearings. But the true problem lies somewhere in this complex urban web. Street vending is an inherent part of the cultural and urban fabric, yet they seem dubiously out of place. Why?

THE NEED

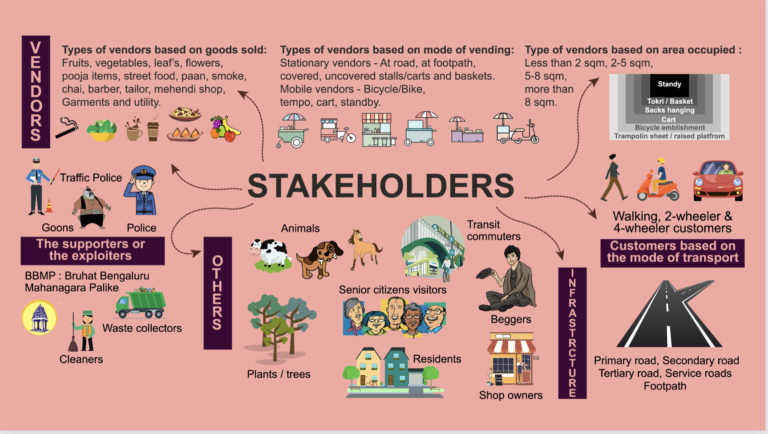

While a few cities have attempted with designated vending zones as solution pathways, it does not solve the problem of out of place vending on many streets within these cities. Recognising this, Auom conducted a Need-Assessment Study to better understand this problem. The study was conducted from multiple stakeholder lens including: spatial design approach to street vending, street vendors’ perspective of their ‘workplace’, their experiences and choices on where and why to vend, customers’ perspective and that of traffic policemen and Urban Local Bodies (ULBs).

Insights from the study revealed the following:

- Many street vendors are still unaware of the legal status of their profession

- Designated vending zones stem from the colonial ideology of segregated space and formalisation of work. This may be a viable solution for planned, wide streets and for vendors who can register. But migrant vendors and others who cannot register (such as older women or temp vendors) will be left out, exposing them to eviction, displacement or dislodgement from their livelihood.

- Similarly, certain misconceptions and biases as well come in the way of inclusive solution approach. For example, in the absence of designated spaces and good road design, street vending is presently managed in spaces where it is possible. Leading them to sometimes cause congestion. But there is a common perception that vendors are the sole cause for congestion. Perception also existing where vending is considered dirty. These deep rooted biases and perceptions across stakeholders drive decisions to evict and exclude rather than finding inclusive solution pathways.

LEVERAGE POINTS FOR AN INCLUSIVE IMPACT

Informed by the need-assessment study Auom has identified the following leverage points for intervention:

– Empowerment of street vendors with knowledge and awareness on policies and schemes in support of their profession.

– Narrative and perception change about street vending and street vendors, across city stakeholders

– A Multi-stakeholder, participatory approach to street designing that is inclusive and resilient to climate impact on street vendors

Auom is now scheduled to carry forward these insights to design and deployment of interventions through multi-stakeholder involvement and participatory methods.

PROJECT STATUS

Seeking further funding